Post by Blitz on Sept 19, 2022 11:28:35 GMT -5

The secret to recent Ukrainian battlefield success? New ‘artillery for dummies’

09-16-22 - BY JESUS DIAZ

www.fastcompany.com/90778767/the-secret-to-recent-ukrainian-battlefield-success-new-artillery-for-dummies

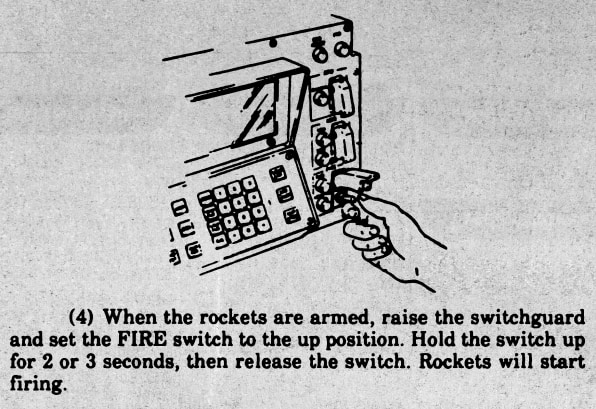

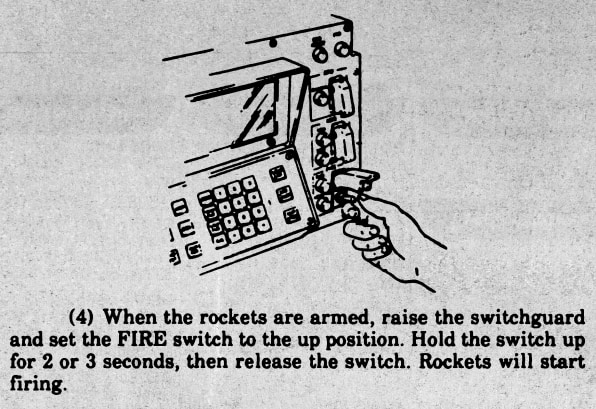

The user interface of HIMARS seems complex when you look at the manuals, but thanks to its computer system, it requires only a few key punches to set a target and fire the rockets.

[Photos: Pfc. Sarah Pysher/USMC/DVIDS, LCpl Nicholas Guevara/USMC/DVIDS]

The Russians are on the run in Ukraine. They are fleeing so fast that they are leaving their weapons behind as the Ukranians take back 1,160 square miles of their territory—and counting. Most experts have called it a “stunning” play and “the greatest counteroffensive since World War II.” It has been the product of the Ukranians’ unfaltering courage against all odds and a clever deception campaign but, the cornerstone of their success has been a war machine called HIMARS.

images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_596,c_limit,q_auto:best,f_webm/wp-cms/uploads/2022/08/18-90778767-this-is-how-soldiers-actually-use-the-himars-weapons-system.gif

images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_596,c_limit,q_auto:best,f_webm/wp-cms/uploads/2022/08/18-90778767-this-is-how-soldiers-actually-use-the-himars-weapons-system.gif

[Image: Sgt. Joseph McDonald/US Army/DVIDS]

Short for High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, HIMARS is a compact truck with a launcher capable of using different types of GPS-guided missiles to hit targets up to 50 miles away. The launchers are extremely powerful, able to obliterate buildings with an explosive firestorm within seconds. They are also fast to set up and use—capable of becoming ready to attack in just a few minutes, fire missiles in a snap, and quickly close shop to abandon their position, avoiding being targeted by the enemy.

Despite its complicated-looking interface, HIMARS features a computer-aided operation and straightforward instruction, which have been a decisive factor in the success of Ukraine’s counteroffensive operation.

[Photo: Cpl Patrick King/USMC/DVIDS]

“ARTILLERY FOR DUMMIES”

The U.S. started to send HIMARS units to Ukraine back in June. By the end of July, the Ukrainian army had fielded 16 units. Only a few days later, on August 3, multiple reports started to appear, describing Russian command centers and logistical depots being destroyed by HIMARS batteries. Ukraine was wreaking havoc all over the Russian lines, cutting their ability to resupply. By the end of the month, it was clear that the weapons were critical for turning the tide of the war. They have proven so effective, in fact, that the Russian Ministry of Defense Sergei Shoigu ordered their destruction as a top priority for his troops.

Impressively, despite having no previous experience with HIMARS systems, the Ukrainian military operators were quickly successful. Though their artillerymen were well versed in operating Soviet-era howitzers and surface-to-air missile units, HIMARS was a completely new weapon. Yet, in just a few days, they were smashing Russian positions.

[Photo: Sgt. Vontrae Hampton/U.S. Army Reserve/DVIDS]

As U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Col. Jon O’Gorman, a military professor at the U.S. Naval War College, told me over video conference, the reason is quite simple: “HIMARS is artillery for dummies.” O’Gorman, who, as a field artillery officer, used HIMARS units in Iraq and Syria, where he was a fire support chief during Operation Inherent Resolve. He also supervised HIMARS units in Afghanistan, targeting the Taliban at various locations.

He explains that HIMARS is so easy to operate that anyone can learn to fire its missiles in no time. If you look at the manuals online, it looks complicated because it has so many knobs and buttons. This seems more complicated than a traditional artillery system, which is a simpler mechanical system, but Gorman explains that the actual operation of selecting a target and firing on HIMARS is comparably easy versus the multi-step mathematics involved in aiming a weapon like a howitzer.

[Photo: Spc. Hannah Frenchick/U.S. Army/DVIDS]

THE CLASSIC HOWITZER WAS TRICKY TO USE

The classic howitzer, a long-range piece of artillery that shoots in an arcing trajectory, was developed in the 16th century as an alternative to cannons, which fire in a flat trajectory. Firing the howitzer requires knowledge of a great number of technical operations. Basically, the operator first needs to set up a grid on a map, knowing where they are. Then they need to get some information from reconnaissance soldiers or airplane pilots about where the target is within that grid. After placing the target on the grid, they start having to make lots of calculations, solving equations to create a firing solution attending to direction, distance, and atmospheric conditions (air density, temperature, and wind). These factors can all affect the projectile’s course on its way to the target. The calculations inform the operator of where to aim the artillery. To actually physically aim, however, they spin knobs and wheels that activate a mechanical or hydraulic system to move the piece of artillery left or right and up or down. They then load your typical 155mm projectile, brace, and fire.

[Photo: Lance Cpl. Juan Magadan/USMC/DVIDS]

Typically, the first shot may fail. At that point, the operator receives a report telling them by how much the target was missed, which prompts another set of calculations to correct the trajectory. They will repeat this process as many times as necessary until they complete the objective, and the success really depends on the experience of the operator. Newer howitzers have gunnery computers that can help calculate the trajectory, but, at the end of the day, most projectiles used today are just kinetic bombs, pieces of metal that fly a parabolic course. It all requires hard work and, often, trial and error.

[Photo: Rachel Gray/Program Executive Office Missiles and Space/DVIDS]

THE HIMARS USER EXPERIENCE PRIORITIZES AUTOMATION

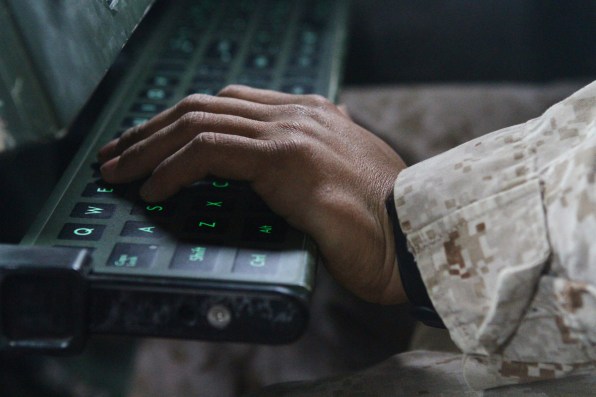

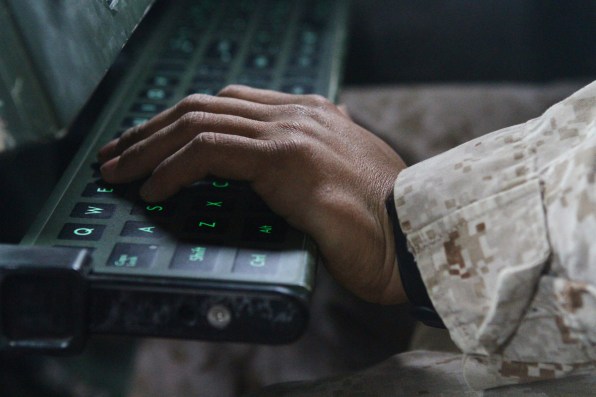

With HIMARS, most of these steps are eliminated, thanks to its computer and the use of GPS. There are no calculations to be made. No feeling the wind or checking the temperature. There are only coordinates. And, in American units, operators don’t even have to enter the coordinates themselves, O’Gorman points out: An operator from a fire direction center beams them to your HIMARS unit through an encrypted channel. Once the operator gets the order to fire, they just need to make sure the launcher is pointing in the general direction of the target, that everything is connected, that they assign a number of missiles to the target, lift the safety, and, “[the operators] just press the button, and then the rockets launch,” O’Gorman says.

[Photo: LCpl Nicholas Guevara/USMC/DVIDS]

At that point, the computer built into the rocket gets the control, guiding itself with its built-in GPS unit, little control wings, and gyroscopes to reach its target. And, unlike the howitzers, they never miss. If the target coordinates are correct, and there’s no system failure, the target is obliterated.

According to Christina Valecillos, senior communications manager for Lockheed Martin, the HIMARS manufacturer, the system went through rigorous usability testing before entering service in 2005. “We worked closely with the [armed services] to ensure HIMARS met all customer requirements to include end user needs,” she said. “This included live-fire events at White Sands Missiles Range in New Mexico, conducted by soldiers.” She offers that these tests “regularly take in user inputs and feedback from the customer and end users to incorporate into future upgrades.”

The company wouldn’t disclose who conducted any usability testing beyond saying that “efforts were completed in partnership with Lockheed Martin, our suppliers, the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps; and operational testing was conducted with Army units to certify the system.”

Fire Control system, circa 1998 [Photo: Spc. Russell J. Good/US Army]

To validate systems like HIMARS, the Army Research Laboratory (ARL) conducts its own usability testing, measuring how easily users can memorize different processes necessary to run these machines. In a 95-page report published in 1996, titled “Training Effectiveness Evaluation of an MLRS Fire Control Panel Trainer Using Distributed Interactive Simulation,” the ARL shows quite thoughtful and thorough methodology to test the first control and targeting system on the HIMARS predecessor, the Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS), where the first Fire Control System debuted (Ukraine is also using 10 MLRS units in the current war, donated by NATO countries).

If the ARL found that the device is not working as it should to ensure good, fluid operation in the high-stress environment of the battlefield, it wouldn’t be operative today. As Valecillos points out, “[the UX testing] process followed milestones for a major defense acquisition program (MDAP). We incorporate metrics and feedback into each design phase.” Even after HIMARS entered service in 2010, she says, they kept adding retrofits and upgrades based on further feedback and the addition of new capabilities.

1998 FCS manual [Image: U.S. Army]

BUILDING ON THE PAST

Ken Shirriff—a noted computer historian famous for restoring an Apollo Guidance Computer—told me via email that the HIMARS’ targeting system evolved from that 1996 Fire Control System (FCS). It is, for now, the culmination of a long lineage of computer-assisted gunnery devices: “The HIMARS and MLRS user interfaces are essentially the same. The fire control system went through various revisions: FCS (fire control system), IFCS (Improved FCS), UFCS (Universal FCS), and CFCS (Common FCS).”

[Image: U.S. Army]

The photo above—taken from an unclassified presentation by Col. Chris Mills, U.S. Army project manager for Precision Fire Rocket and Missile Systems—displays the CFCS, which is presumably inside the HIMARS that Ukrainian forces are using against the Russians. “Note the black programmable function keys around the screen, pointing to the green labels on the screen,” Shirriff says. “The user interface looks somewhat unpleasant, with a lot of pressing programmable function keys to move through menus.” Yet, while the interface is ugly, its effectiveness in the battlefield is undeniable.

[Photo: 118th Wing/Tennessee Air National Guard]

Looking at a training evaluation report from 2002, operating a HIMARS is clearly not as straightforward as picking up an iPhone and tapping icons. But then, that’s also part of its nature. The keys are very similar to the ones you can find on the frames of the screens in other military systems, like on fighter jets’ cockpits, as well as civilian airplanes and ships. Instead of abstracting controls under layers of menus or deep settings, these keys allow for fast, direct access to the machine’s many functions.

[Photo: Photo by Sgt. Jacob Harrer/USMC/DVIDS]

THE UKRAINIAN MOTIVATION FACTOR

However one might critique the spartan ugliness of the HIMARS interface, as O’Gorman points out, the proof is on the battlefield: “The time between the [HIMARS] units arriving and the first results of things being destroyed was short. They took like a hundred targets, according to the Pentagon in the first few days of using these systems. So they were pretty effective.” That tells him that their experience must have been similar to what happened to him the first time he got into a HIMARS cabin in Syria. The unit commander gave him a quick tour on how the whole thing operated, and he figured it out on the spot.

A Ukrainian serviceman behind the wheel of a HIMARS, circa 2022 [Photo: Anastasia Vlasova/The Washington Post/Getty Images]

For O’Gorman, it’s obvious that the Ukrainians have figured out the system in record time. In the U.S., the training to use HIMARS takes several weeks, he says. But with the right motivation—which the Ukrainians have—it can take a lot less. “You’re probably taking Ukrainian soldiers who have been trained as artillerymen, so they know the process of an artillery piece or a mortar piece,” he points out. “Converting that knowledge into using the HIMARS is not that big of a change.” But motivation alone wouldn’t have been enough if they had a weapon that was hard to use. Ultimately, the Ukrainian forces’ lightning success adapting to this system and turning the tide of the war is a testament to HIMARS’ UX counterintuitive effectiveness.

09-16-22 - BY JESUS DIAZ

www.fastcompany.com/90778767/the-secret-to-recent-ukrainian-battlefield-success-new-artillery-for-dummies

The user interface of HIMARS seems complex when you look at the manuals, but thanks to its computer system, it requires only a few key punches to set a target and fire the rockets.

[Photos: Pfc. Sarah Pysher/USMC/DVIDS, LCpl Nicholas Guevara/USMC/DVIDS]

The Russians are on the run in Ukraine. They are fleeing so fast that they are leaving their weapons behind as the Ukranians take back 1,160 square miles of their territory—and counting. Most experts have called it a “stunning” play and “the greatest counteroffensive since World War II.” It has been the product of the Ukranians’ unfaltering courage against all odds and a clever deception campaign but, the cornerstone of their success has been a war machine called HIMARS.

images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_596,c_limit,q_auto:best,f_webm/wp-cms/uploads/2022/08/18-90778767-this-is-how-soldiers-actually-use-the-himars-weapons-system.gif

images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_596,c_limit,q_auto:best,f_webm/wp-cms/uploads/2022/08/18-90778767-this-is-how-soldiers-actually-use-the-himars-weapons-system.gif[Image: Sgt. Joseph McDonald/US Army/DVIDS]

Short for High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, HIMARS is a compact truck with a launcher capable of using different types of GPS-guided missiles to hit targets up to 50 miles away. The launchers are extremely powerful, able to obliterate buildings with an explosive firestorm within seconds. They are also fast to set up and use—capable of becoming ready to attack in just a few minutes, fire missiles in a snap, and quickly close shop to abandon their position, avoiding being targeted by the enemy.

Despite its complicated-looking interface, HIMARS features a computer-aided operation and straightforward instruction, which have been a decisive factor in the success of Ukraine’s counteroffensive operation.

[Photo: Cpl Patrick King/USMC/DVIDS]

“ARTILLERY FOR DUMMIES”

The U.S. started to send HIMARS units to Ukraine back in June. By the end of July, the Ukrainian army had fielded 16 units. Only a few days later, on August 3, multiple reports started to appear, describing Russian command centers and logistical depots being destroyed by HIMARS batteries. Ukraine was wreaking havoc all over the Russian lines, cutting their ability to resupply. By the end of the month, it was clear that the weapons were critical for turning the tide of the war. They have proven so effective, in fact, that the Russian Ministry of Defense Sergei Shoigu ordered their destruction as a top priority for his troops.

Impressively, despite having no previous experience with HIMARS systems, the Ukrainian military operators were quickly successful. Though their artillerymen were well versed in operating Soviet-era howitzers and surface-to-air missile units, HIMARS was a completely new weapon. Yet, in just a few days, they were smashing Russian positions.

[Photo: Sgt. Vontrae Hampton/U.S. Army Reserve/DVIDS]

As U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Col. Jon O’Gorman, a military professor at the U.S. Naval War College, told me over video conference, the reason is quite simple: “HIMARS is artillery for dummies.” O’Gorman, who, as a field artillery officer, used HIMARS units in Iraq and Syria, where he was a fire support chief during Operation Inherent Resolve. He also supervised HIMARS units in Afghanistan, targeting the Taliban at various locations.

He explains that HIMARS is so easy to operate that anyone can learn to fire its missiles in no time. If you look at the manuals online, it looks complicated because it has so many knobs and buttons. This seems more complicated than a traditional artillery system, which is a simpler mechanical system, but Gorman explains that the actual operation of selecting a target and firing on HIMARS is comparably easy versus the multi-step mathematics involved in aiming a weapon like a howitzer.

[Photo: Spc. Hannah Frenchick/U.S. Army/DVIDS]

THE CLASSIC HOWITZER WAS TRICKY TO USE

The classic howitzer, a long-range piece of artillery that shoots in an arcing trajectory, was developed in the 16th century as an alternative to cannons, which fire in a flat trajectory. Firing the howitzer requires knowledge of a great number of technical operations. Basically, the operator first needs to set up a grid on a map, knowing where they are. Then they need to get some information from reconnaissance soldiers or airplane pilots about where the target is within that grid. After placing the target on the grid, they start having to make lots of calculations, solving equations to create a firing solution attending to direction, distance, and atmospheric conditions (air density, temperature, and wind). These factors can all affect the projectile’s course on its way to the target. The calculations inform the operator of where to aim the artillery. To actually physically aim, however, they spin knobs and wheels that activate a mechanical or hydraulic system to move the piece of artillery left or right and up or down. They then load your typical 155mm projectile, brace, and fire.

[Photo: Lance Cpl. Juan Magadan/USMC/DVIDS]

Typically, the first shot may fail. At that point, the operator receives a report telling them by how much the target was missed, which prompts another set of calculations to correct the trajectory. They will repeat this process as many times as necessary until they complete the objective, and the success really depends on the experience of the operator. Newer howitzers have gunnery computers that can help calculate the trajectory, but, at the end of the day, most projectiles used today are just kinetic bombs, pieces of metal that fly a parabolic course. It all requires hard work and, often, trial and error.

[Photo: Rachel Gray/Program Executive Office Missiles and Space/DVIDS]

THE HIMARS USER EXPERIENCE PRIORITIZES AUTOMATION

With HIMARS, most of these steps are eliminated, thanks to its computer and the use of GPS. There are no calculations to be made. No feeling the wind or checking the temperature. There are only coordinates. And, in American units, operators don’t even have to enter the coordinates themselves, O’Gorman points out: An operator from a fire direction center beams them to your HIMARS unit through an encrypted channel. Once the operator gets the order to fire, they just need to make sure the launcher is pointing in the general direction of the target, that everything is connected, that they assign a number of missiles to the target, lift the safety, and, “[the operators] just press the button, and then the rockets launch,” O’Gorman says.

[Photo: LCpl Nicholas Guevara/USMC/DVIDS]

At that point, the computer built into the rocket gets the control, guiding itself with its built-in GPS unit, little control wings, and gyroscopes to reach its target. And, unlike the howitzers, they never miss. If the target coordinates are correct, and there’s no system failure, the target is obliterated.

According to Christina Valecillos, senior communications manager for Lockheed Martin, the HIMARS manufacturer, the system went through rigorous usability testing before entering service in 2005. “We worked closely with the [armed services] to ensure HIMARS met all customer requirements to include end user needs,” she said. “This included live-fire events at White Sands Missiles Range in New Mexico, conducted by soldiers.” She offers that these tests “regularly take in user inputs and feedback from the customer and end users to incorporate into future upgrades.”

The company wouldn’t disclose who conducted any usability testing beyond saying that “efforts were completed in partnership with Lockheed Martin, our suppliers, the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps; and operational testing was conducted with Army units to certify the system.”

Fire Control system, circa 1998 [Photo: Spc. Russell J. Good/US Army]

To validate systems like HIMARS, the Army Research Laboratory (ARL) conducts its own usability testing, measuring how easily users can memorize different processes necessary to run these machines. In a 95-page report published in 1996, titled “Training Effectiveness Evaluation of an MLRS Fire Control Panel Trainer Using Distributed Interactive Simulation,” the ARL shows quite thoughtful and thorough methodology to test the first control and targeting system on the HIMARS predecessor, the Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS), where the first Fire Control System debuted (Ukraine is also using 10 MLRS units in the current war, donated by NATO countries).

If the ARL found that the device is not working as it should to ensure good, fluid operation in the high-stress environment of the battlefield, it wouldn’t be operative today. As Valecillos points out, “[the UX testing] process followed milestones for a major defense acquisition program (MDAP). We incorporate metrics and feedback into each design phase.” Even after HIMARS entered service in 2010, she says, they kept adding retrofits and upgrades based on further feedback and the addition of new capabilities.

1998 FCS manual [Image: U.S. Army]

BUILDING ON THE PAST

Ken Shirriff—a noted computer historian famous for restoring an Apollo Guidance Computer—told me via email that the HIMARS’ targeting system evolved from that 1996 Fire Control System (FCS). It is, for now, the culmination of a long lineage of computer-assisted gunnery devices: “The HIMARS and MLRS user interfaces are essentially the same. The fire control system went through various revisions: FCS (fire control system), IFCS (Improved FCS), UFCS (Universal FCS), and CFCS (Common FCS).”

[Image: U.S. Army]

The photo above—taken from an unclassified presentation by Col. Chris Mills, U.S. Army project manager for Precision Fire Rocket and Missile Systems—displays the CFCS, which is presumably inside the HIMARS that Ukrainian forces are using against the Russians. “Note the black programmable function keys around the screen, pointing to the green labels on the screen,” Shirriff says. “The user interface looks somewhat unpleasant, with a lot of pressing programmable function keys to move through menus.” Yet, while the interface is ugly, its effectiveness in the battlefield is undeniable.

[Photo: 118th Wing/Tennessee Air National Guard]

Looking at a training evaluation report from 2002, operating a HIMARS is clearly not as straightforward as picking up an iPhone and tapping icons. But then, that’s also part of its nature. The keys are very similar to the ones you can find on the frames of the screens in other military systems, like on fighter jets’ cockpits, as well as civilian airplanes and ships. Instead of abstracting controls under layers of menus or deep settings, these keys allow for fast, direct access to the machine’s many functions.

[Photo: Photo by Sgt. Jacob Harrer/USMC/DVIDS]

THE UKRAINIAN MOTIVATION FACTOR

However one might critique the spartan ugliness of the HIMARS interface, as O’Gorman points out, the proof is on the battlefield: “The time between the [HIMARS] units arriving and the first results of things being destroyed was short. They took like a hundred targets, according to the Pentagon in the first few days of using these systems. So they were pretty effective.” That tells him that their experience must have been similar to what happened to him the first time he got into a HIMARS cabin in Syria. The unit commander gave him a quick tour on how the whole thing operated, and he figured it out on the spot.

A Ukrainian serviceman behind the wheel of a HIMARS, circa 2022 [Photo: Anastasia Vlasova/The Washington Post/Getty Images]

For O’Gorman, it’s obvious that the Ukrainians have figured out the system in record time. In the U.S., the training to use HIMARS takes several weeks, he says. But with the right motivation—which the Ukrainians have—it can take a lot less. “You’re probably taking Ukrainian soldiers who have been trained as artillerymen, so they know the process of an artillery piece or a mortar piece,” he points out. “Converting that knowledge into using the HIMARS is not that big of a change.” But motivation alone wouldn’t have been enough if they had a weapon that was hard to use. Ultimately, the Ukrainian forces’ lightning success adapting to this system and turning the tide of the war is a testament to HIMARS’ UX counterintuitive effectiveness.